“Keny Whitright’s influence on the concert lighting business cannot be overstated,” says Marshall Bissett, founder of the lighting supply company TMB. “From the first color changers to Coloram, Cygnus LED fixture, and Autopilot tracking system, he was the problem-solving pioneer. His products ruled Broadway and the touring market because they worked hard and reliably.”

Whitright is the inventor of the color scroller, a product that, while more than 40 years old, is still in use. But he has been prolific throughout his career. In 1983 he built an automated hoist system. “Genesis wanted to control 18 hoists over the artists and be able to run them in the dark—scary stuff,” he says. But nothing scared Whitright.

Whitright has a longtime colleague and friend in Jim Bornhorst—even though at one point they became competitors. “He taught me to fly fish,” says Bornhorst, who was honored with this award in 2010. “We called him ‘boy wonder’ for a reason. He earned that moniker because he was so good at everything he did. He would tackle something and make it work.”

A Pivotal Experience

Whitright grew up in Wichita, KS, where he got a job at the local Hi-Fi shop. But his first official job in this business was for the local live sound company, Superior Sound (today known as Galaxy Audio). Despite not being “terribly technical” at the time, he was hired to service the equipment. One night he went to a Three Dog Night show, and he met Showco co-founder Jack Maxson. A brief conversation ensued, and Whitright was intrigued with the work Showco was doing. Later he and a coworker went down to Dallas to pick up a Heathkit oscilloscope kit. They had time to kill, so they stopped by Showco’s HQ. Whitright was offered a job on the spot. In December of 1971, he moved to Dallas and started working for them.

Showco immediately asked the young man to get a passport, because he was going to Europe to work on a Jesus Christ Superstar production. “That turned out to be a pivotal experience.” A group out of Columbus, OH had toured the states for a couple of years with an Ohio-based crew headed by the show’s designer, technical director, and stage manager, Kirby Wyatt. Astonishingly, they did this show without ever getting the rights to perform it. “It was a great production, and then they decided to take it to Europe.” The lighting and sound guy didn’t want to go, so the group reached out to Showco, and off Whitright and co-worker Kevin McNevins went. “But it turned out that while [creators] Andrew Lloyd Weber and Tim Rice had terrible lawyers in the States, they had great ones in Europe.” Once over the pond, the production was shut down in 10 days, leaving Whitright and McNevins stranded. Then something pretty crazy happened: They got hooked up with another (legal) production of Jesus Christ Superstar out of Sweden and worked that show for seven weeks. It gave Whitright valuable front-line production experience.

Bornhorst says the two met at Showco in 1972—Bornhorst as an electrical engineer to “design electronic stuff” and Whitright as an FOH audio engineer. They started out as “sound guys,” and Whitright got involved in the technical aspect of Showco working with Bornhorst on whatever was needed. (This was back in the day when production houses built their own gear). “Keny had the ability to learn and apply knowledge quickly and effectively,” Bornhorst says. “He got involved in the electronic equipment and components I was building, and I had a lot of respect for him because it was not trivial work.”

“We had an unusually talented group of people at Showco at the time, and that included Keny,” says Showco’s owner and founder Rusty Brutsché. “He was always multi-talented, smart, and eager to dive into whatever was going on.” He adds while Whitright’s innovations in lighting are well-known, he also contributed to the audio. “He was also quite good at acoustics and designed some of our speaker cabinets including the ‘Hurler,’ a 600W four 15” speaker cabinet that was a big part of our inventory at the time.” (Why Hurler? “It was so loud it made you want to throw up.”) During this period, Whitright was also part of Showco’s outdoor staging efforts. “He was great at managing that. He is always inventive, adaptable, and good at a lot of things.”

Also in 1972, Showco added lighting to their touring services, and Whitright and McNevins recommended Wyatt to run the lighting department (in fact, that entire Jesus Christ Superstar crew were hired on). But that expansion soon stalled. “The lighting department was getting its ass kicked by English companies, because our systems used big dimmers and bigger cables,” Whitright says. “Kirby said that if we had a way to change the colors on the PAR cans, we could differentiate ourselves from the limeys.”

Bissett, a self-proclaimed limey, confirms a “huge” shift in technology that took place in the late 1970s. “We went from using hand-me-down American theater technology to a dimmer-per-circuit format with Socapex multicores that only needed to carry 1,000W loads. Compact dimmers, pioneered by Alderham and Avolites in the UK, made possible the huge PAR can rigs of Van Halen, Queen, and others. TMB was founded on the idea of importing this gear from England and promoting it to the U.S. touring market.”

Whitright says it was Wyatt who laid out the specs for the lighting accessory that was needed: it had to fit on a PAR 64, have random access colors, and change in 1/10th of a second. “We made a lot of attempts [on a color changer] with Showco, hiring industry and non-industry people to help,” says Bornhorst. “One was Rusty Brutsché’s mentor, George Cason, who came from the oil industry with a background in mechanics and physics.” Others were cycled through, but the challenge of creating something that could change color always remained in Bornhorst’s and Whitright’s in-box. “The hardest requirement was creating something where the color could change within that 10th of a second—that was a helluva challenge.”

Ideas percolated for a couple of years. This included the idea of having six separate motors (solenoids) to instantly release and add color à la a followspot. “The gel frame model for the PAR 64 was our obstruction,” Whitright says. Also, the prototypes made were too heavy. “Then the first one we got to work ran off air pressure. But the idea of folks carrying air compressors on the road did not go over well.” Eventually someone thought of a smaller PAR model “where we could apply voltage to a crystal” that would change colors. They also gave a liquid filter some consideration. The thickness of the filter would change to vary the saturation of the filter. “Jim and I worked on different color changer projects during which we mostly learned what didn’t work,” Whitright quips.

In 1978, Whitright left Showco to work for a local club called Rick & Neal’s. “I was hired to run lights only because they knew I could also fix the sound system. I eventually became an acceptable operator.” He was working with little reflector bulbs that were in just four different colors. “That’s when I realized what Kirby was talking about, and I saw why something better was needed.”

Inventing the Scroller

It was winter of 1978 when he started tinkering with the scroller idea and built a conceptual model. “I had a piece of aluminum C-channel, some rollers and circuitry that could digitally move the gels from one position to the next in the string,” Whitright explains.

In 1979, Mike Brown of the California-based staging company United Production Services, needed a staging depot in Dallas and reached out to Whitright. Unable to incorporate Brown’s company’s name in Texas, at the spur of the moment the two settled on a combination of their names: Wybron. This would be the company name for the Colormax, the first scrolling color changer and other products.

That next year in March, Lighting Designer and friend Jim Lenahan, with Dave “Obie” Oberman and Kevin Wall from United Production Services, visited Whitright in Dallas. “They were looking for something new for an upcoming Tom Petty tour,” Whitright says. “They liked the idea of what I was working on and ordered some. I then had 60 to 90 days to take the prototype to manufacturing and deliver them to the tour. I threw the first six in a road case with a controller we designed and delivered them to Obie’s Lighting in California. The Colormax was born.”

Another friend who would be key to the next development was award-winning Lighting Designer Allen Branton. They met in 1973 when both were touring with the Beach Boys—Whitright as senior sound engineer, and Branton on his first tour as a lighting designer. “We were on the road together virtually from the very beginning of both our careers,” Branton says. They too became fishing buddies, and that’s when Branton first heard talk of this “color-changing light idea,” Branton adds. “He created something dynamic and exciting for those arena shows without the weight and power needs of PAR cans.”

In 1981, Branton was going to light the Rolling Stones’ American Tour with this new Wybron product. “We got our hands on 12 of some of the first Colormax and we pulled them out of the box.” Included were instructions on how to create a gel strip. Per the instructions, they decided what 10 colors they wanted and in what order, and part of the prep work on those was sizing, cutting, and taping those gels just right. “We learned that the gel string needed to be cut perfectly straight and be perfectly taped.” When they were put in the overhead rig, Branton realized they did not achieve that objective. He ended up putting them on the ground, six on each side of the stage, which worked for that show. But typical of Whitright, when he was told of this problem, he immediately went to work fixing it. “Keny then created a system where he could create absolutely flawless gel strings.” Wybron then went onto have a successful side business building those strings for customers who bought the Colormax.

One of Branton’s long time clients was Diana Ross, who did up to six-week stints in Vegas. These were big shows, with 30 musicians, all dressed in white on a white stage set, with Ross also in white. “So color becomes really powerful in that setting, and a high point was using Keny’s scrollers to do things like wash everything in blue.”

“The color scroller was a brilliant product filling an important need in theater and touring,” Brutsché says. “It was clever how he came up with the idea of taping the gels together—it was a good, simple, reliable scheme.”

A True Home Run

Next Whitright came up with the ColorWiz, a lighter, less expensive scroller. They hit that latter goal a little too well. “Unfortunately, we made too tight a deal, so the ColorWiz was kind of limited.” At this point, both the Colormax and ColorWiz were both promoted by Great American Market. Then Whitright decided to market the color changers on his own in 1984 and met Don Stern, President of BASH Lighting, a theatrical lighting company that did a lot of Broadway work. “He said he would be my biggest customer and wanted the best price—I thought, ‘yeah, right!’” Whitright says. “It turned out to be true. At that time before the great consolidation of rental shops on Broadway, there were four main shops: BASH, Four Star, Vanco, and Production Arts. Don Stern lead the way with our DMX version of the scroller by promoting them heavily.”

The next evolution in his scroller development was the Coloram, a faster, quieter scroller. “We built 100 of those, and the first 30 were used by Nautilus Entertainment Design’s Jim Tetlow on a Carnival Cruise ship.” Demand was such that more were needed, and he improved on the first one with the Coloram II. “Pretty much every Broadway theater had Coloram IIs because designers like Ken Billington, Peggy Eisenhauer, Jules Fisher, and Richard Pilbrow used it on all their shows,” Whitright says. “We eventually sold 100,000 units—it was a true home run.”

Billington would first use Wybron products on Broadway in 1982’s Tony Award-winning play Foxfire staring Jessica Tandy. “It was a product that took lighting to the next level,” he says, adding that even though moving lights came out about the same time, he and other Broadway designers preferred the Colorams because moving lights “weren’t readily available, weren’t reliable, and were noisy.” He turned to Wybron scrollers frequently—and for many years. “They were just a workhorse. Honestly, I just took the color scrollers off a production of Chicago where I had been using them there for 25 years.” He asked the rental house, PRG, what they were going to do with them and when they said they would retire them, he asked if they could give them to an off-Broadway theater company he knew of, “and they are still using them.”

Billington has one more story: By 1989, there were scroller competitors, and in designing the Broadway version of Meet Me in St. Louis, he asked for 100 Rainbow color changers from Sweden-based Camelont Productions. They told him they would need up to four months to complete that order. “I told them ‘this is Broadway, I need them in three weeks.’” He then reached out to Whitright. “Yup, we can do that,” Billington was told.

Looking back, Whitright has great appreciation for Wyatt’s contribution. “He came up with the idea of color changing” within those specifications. Because of Wyatt’s directive, two distinctly different but equally industry-changing products were developed. “I don’t think Kirby gets the credit he deserves,” he says. “He didn’t do the work, but it was his idea.”

If a 5-Year-Old Can…

“When we first started in 1980, we weren’t using all our capacity to build Colormax units and fortunately, Bornhorst needed the electronics cards assembled for the first 350 Vari-Lite automated lights. I was the tester, and I got a real taste of the pan and tilt feature.” Whitright thought of using an X & Y system on stage to point the light. With this approach, “once you had a light that could point to the spot, multiple lights could point to the same spot as well. And then you could move the spot and any number of lights, moving together” in unison. He built a couple prototypes and got his young son, Chris, to operate them. “I showed him that by using a trackball, he could move the lights away or towards himself or left and right.” He demonstrated it by putting Chris at the helm and asked him to follow him while he walked around the warehouse. “That showed me that the idea was very powerful. I figured if you could show a five-year old how to use it in 10 minutes, it was a great way to control a machine.” With this technology, and with former Showco associate Jack Calmes, they formed Syncrolite, sending it to market. (Whitright would not stay long with Syncrolite, and moved on shortly after the launch).

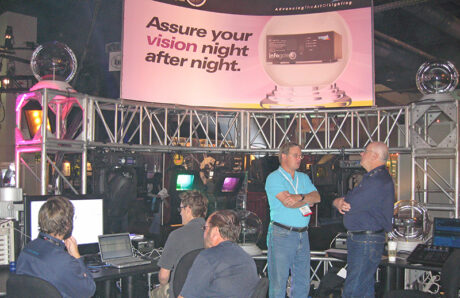

In 1992, Whitright had a booth at PLASA which was not getting a lot of foot traffic. “I was in a funk, wandering the aisles, and thought that there had to be a way to bring people to our booth.” The idea of an artist wearing a transmitter that could be followed by moving lights had been dreamed about by many, and now the previous work with the trackball showed that to be possible. “Back then, there was around 60 days between PLASA and LDI, and we developed the Autopilot in time to show at LDI.” At the next LDI in Dallas, the prototype was demonstrated by a Frisbee with the transmitter, and it got attention; but it would take two years to turn it into a viable product. Whitright built a system that would track up to four artists around stage using up to 55 moving lights, replacing up to four people working followspots. When released in 1994, it won Product of the Year in both Europe (PLASA) and America (LDI), which was unprecedented.

ZZ Top would be the first to take it out on tour, followed by Bon Jovi. Then Billington employed it on the Lily Tomlin’s Tony Award-winning Broadway show, The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe. Whitright would invite Bornhorst and his wife to that show. “During intermission, I told him the followspots were done by Autopilot. He had no idea that it wasn’t being done manually—he practically fell on the floor.” The audience was blown away too. “Tomlin wore the transmitter in her hair, and I had [High End Systems] Studio Beams, Studio Spots, and Cyberlights following her during transitions,” Billington says. He would use Autopilot again when he designed Dance of the Vampires starring Michael Crawford. “It was a great product that no one else had come up with.” While you could justify it when you consider the labor savings of not having manual followspots, the $25,000 price-point proved prohibitive.

RDM and Infotrace

Around 2000, there was an increasing desire for a feedback standard that would allow two-way communication between the board operator and the lights using DMX. ESTA would eventually come up with Remote Device Management (RDM), a protocol enhancement that would become universal. But at that point there were no new products for the new protocol, so Whitright built one. His bi-directional communication device became the Wybron Infotrace Control and Management System. This allowed the operator to know if there was a broken gel string, if it was getting too hot, etc., without ever leaving the computer. Perhaps most advantageous is that it could handle software updates while the light was still up in the truss.

When the LED revolution started, Whitright came up with the Cygnus 100 and 200 LED-based fixtures. “They were fine and dandy, but to the untrained eye, you couldn’t tell the difference from ours and the cheap Chinese imports coming in at the time. Ours sold for $1,600 versus $400—which was less than the cost of materials for ours.” He also spent a lot of “time, money, blood, sweat, and tears—mostly tears at the end” coming up with a product that could compete in the market, but ultimately could not.

When Apple launched its app store 2008, he offered one of the first industry-related apps, the CXI Color Calculator that stimulated the way Wybron’s CXI Color Mixing scroller worked. Next, he came up with Wybron’s Gel Swatch Library app with a collection of nearly 1,700 gels from the four major manufacturers in your hands. Designers could browse, search, and compare to get that perfect shade of purple right from their phone. He would follow this up with ShadowMagic, an app helpful in visualizing lighting on a small stage.

Wybron closed its doors in 2013, though Whitright and a small team continue supplying parts and service to the thousands of his products still in use. And of course, he gets plenty of fishing in with friends and admirers.

“He’s a hard-headed, strong personality who believes what he believes and knows what it takes to be successful,” Brutsché says. “Keny is an absolute prince of a fellow—one of the smartest guys I ever met,” Bornhorst says. “He was a self-taught coder who produced some of the most amazing software. Sure, he’s always been a bit odd, but he’s generous to fault. He took such good care of his people at Wybron. For example, at a company like that, those on the front line don’t get the credit they deserve, but Keny made sure that everyone was appreciated.”